APHRODITE

The Flesh of Desire and Light

The Venus de Milo is the name of one of the most famous works of ancient Greek sculpture.

The Myth from which Everything Begins

Love is not born in silence. It erupts from decay, from the disintegration of power and order. Thus, according to ancient Greek legends, Aphrodite appears not from the womb, but from foam – ethereal and inexplicable. The sea, stirred by a violent divine action, raises to its surface an image that will never sink again: the image of immortal attraction. In an alternative version, she is the daughter of Zeus and the oceanid Dione, but whatever we believe, one thing remains: Aphrodite is not just a goddess. She is a force. An apparition. Something that changes the atmosphere as soon as it enters the room. The love that gives birth to chaos.

Her story is woven of longings, betrayals, rivalries. Married to Hephaestus, creator of weapons and mechanical wonders, but her soul belongs to the fiery Ares, and her body to the one who dared to desire her. Aphrodite does not ask. She demands. Attractive not because she is perfect, but because she embodies the imperfect truth of desire.

Botticelli and the visual return of the goddess

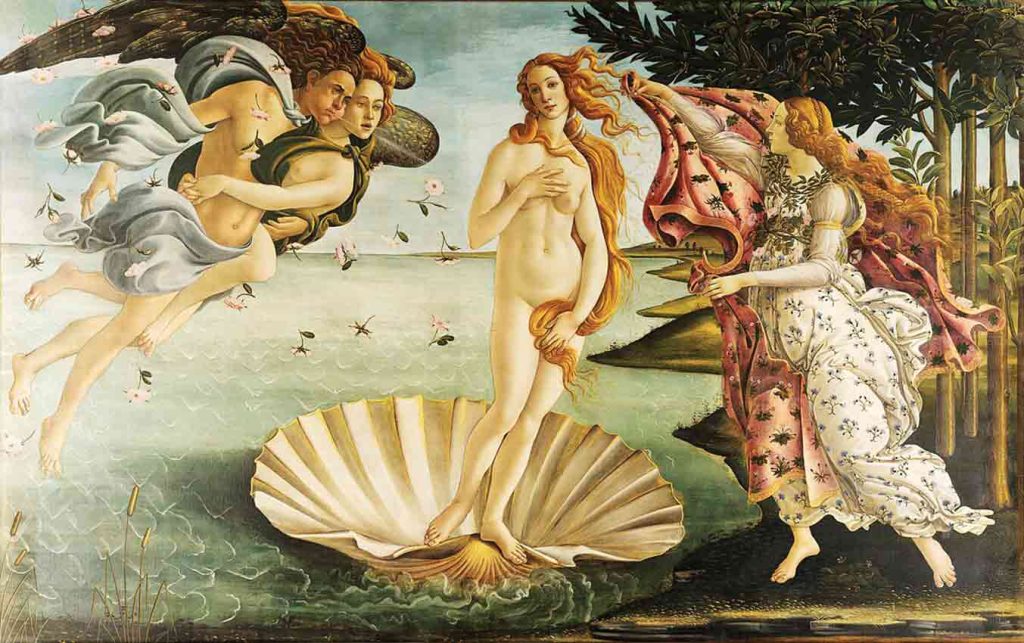

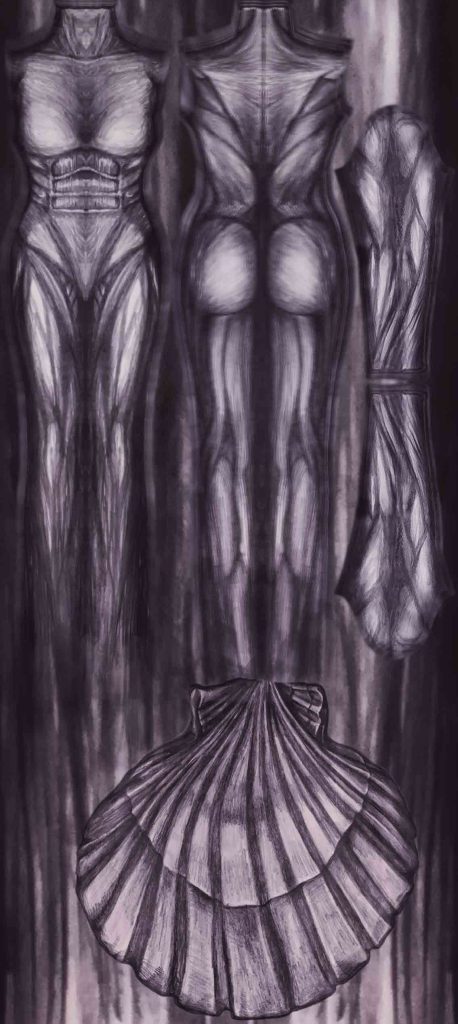

Fifteenth century. The Renaissance reopens the pages of forgotten myths and brings forbidden flesh back to art. It was then that Sandro Botticelli painted what had not been allowed until then: the naked female body, not as a sin, but as a praise. “The Birth of Venus” does not simply depict a myth, it revives it. Venus (the Roman analogue of Aphrodite) appears at the center of the canvas: vulnerable and omnipotent on a giant clam, raised by the waves, surrounded by deities and wind.

The model who inspired this face of the goddess is Simonetta Vespucci: an icon of Florentine beauty, whom Botticelli is said to have continued to paint even after her death. In the painting, Venus is not just a woman, she is an idea, a prototype of a new femininity that does not tolerate submission. Scandalous for its time, the canvas clashes church morality with antique splendor.

The same goddess – different names, different civilizations

The image of Aphrodite has been carried over the centuries, mixed with other mythologies and taken on new faces:

Venus in Rome

Astarte in Phoenicia

Ishtar in Babylon

Inanna in Sumer

Tanit in Carthage

Cybele in Phrygia

Freya in Scandinavia

From myth to decay: Venus in rags

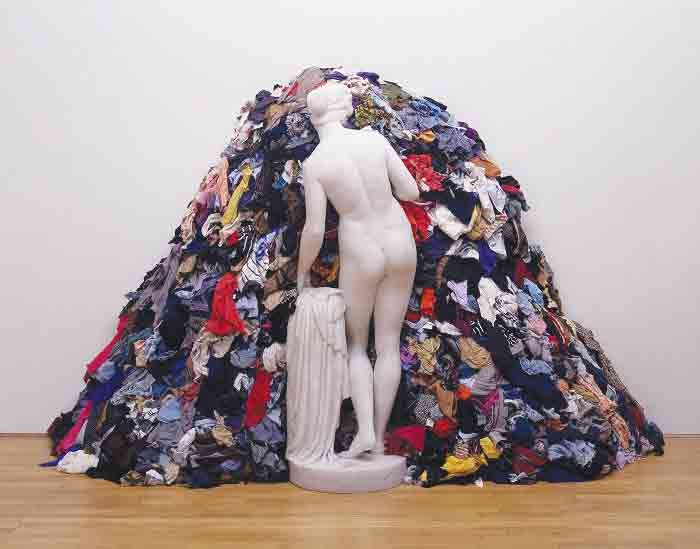

But time marches on, and so do our images. In 1967, Italian conceptualist Michelangelo Pistoletto created the sculpture “Venus in rags,” a cast of a classical antique Venus, placed with her back to the viewer, facing a pile of old clothes, rags, and trash.

The work is part of the Arte Povera movement: an art that uses “poor” materials to resist consumer culture and expose its emptiness. Where Botticelli exalts flesh, Pistoletto places it in the context of oblivion.

Venus no longer looks at the viewer. She has turned away. She is silent. Not because she is defeated, but because she refuses to be part of the spectacle of consumption. Beauty, deified in the past, has been drowned in the noise of the world, in clothes that no one wants to wear anymore. It is a mirror of decay, but also an opportunity for a new reading.

The Two Venuses: The Aesthetic Bridge

Boticelli paints the rise at the moment when the female body is elevated to myth. The pistol shows the ruin, the loss of this body in the labyrinth of consumerism. Between them lies the question: What remains of a woman when her image is used to the point of being erased?

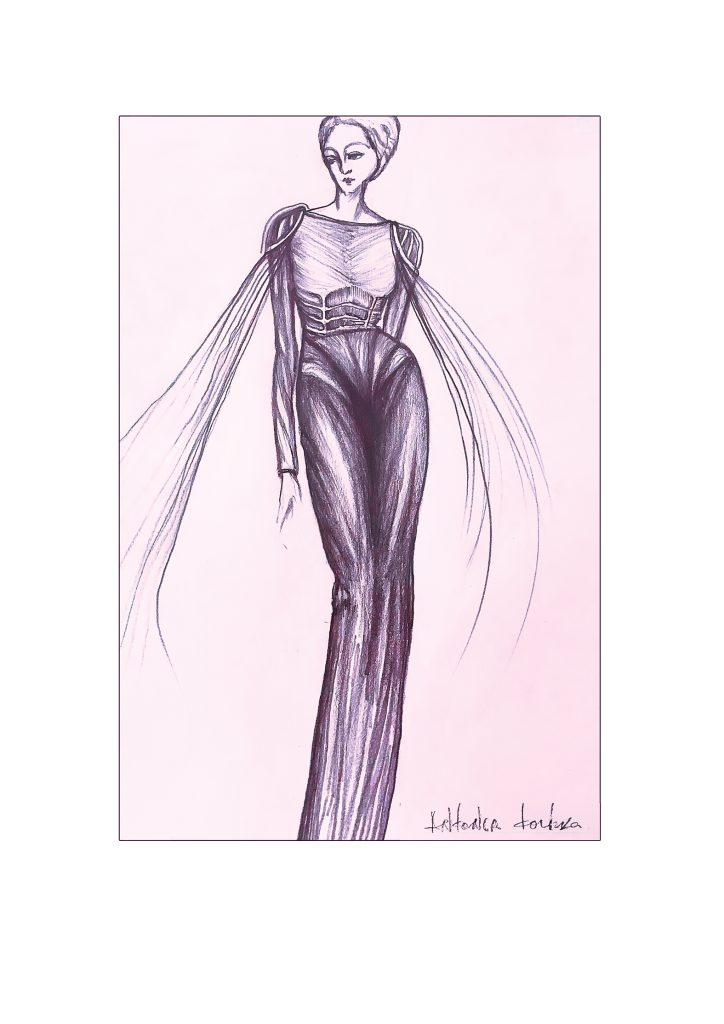

Aphrodite in MetaSelf: the flesh as a path to wholeness

In the concept of MetaSelf, Aphrodite is not just a deity, but an archetype, the original image that speaks to our inner sense of body, beauty and self love.

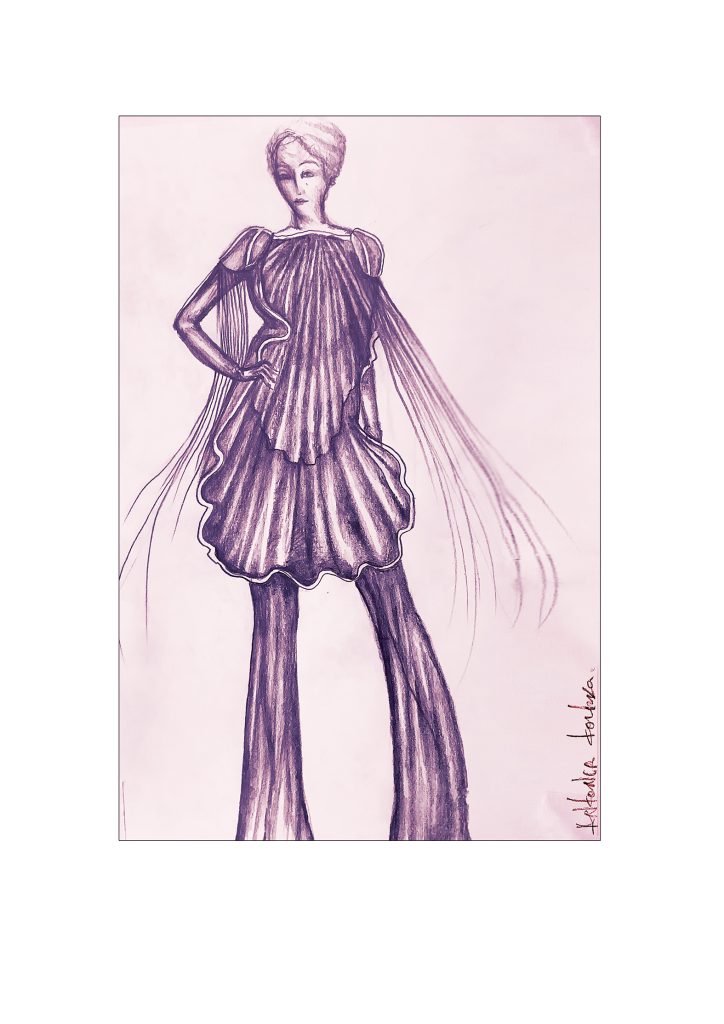

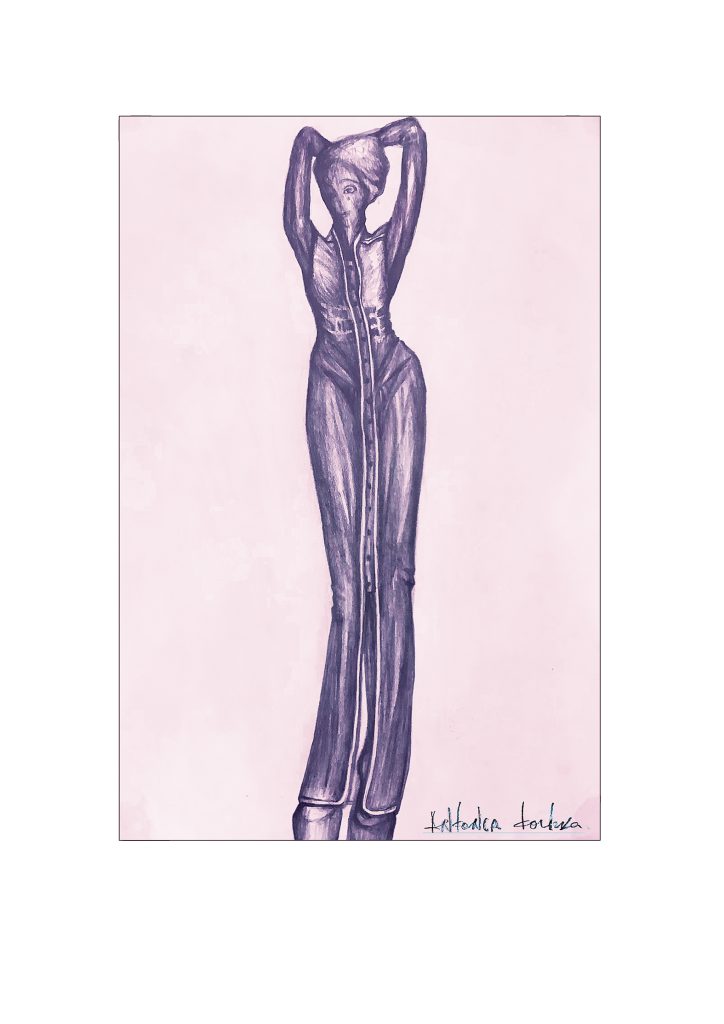

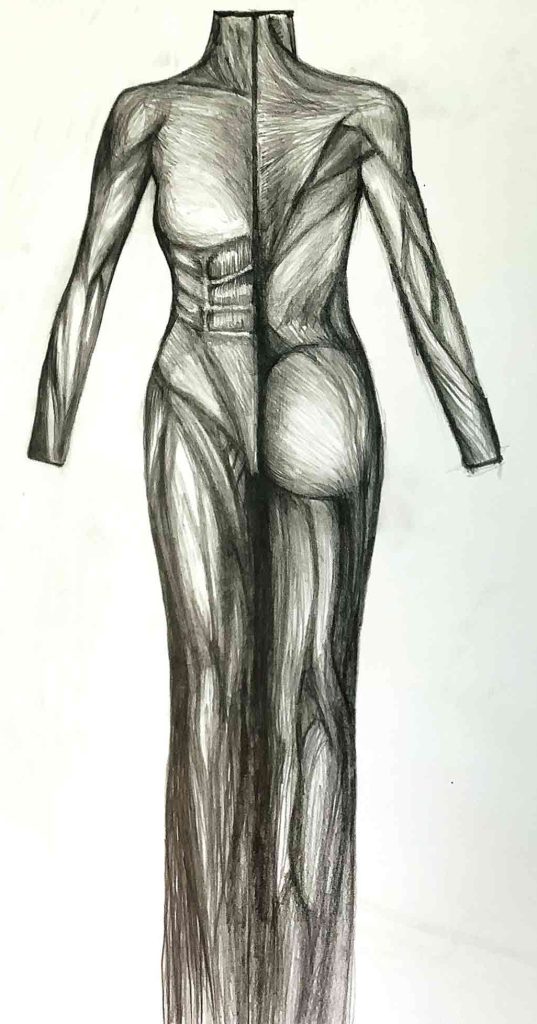

Venus (Aphrodita) solves one of the biggest social traps – imposed beauty, the dictates of plastic interventions. By printing the idealized body and its universal musculature on a dress, sexuality ceases to be binary. Muscle is common to all, the body is an experience, not a gender. Woman and man share the same skeleton, the same muscle, the differences are external.

She is not a symbol of seduction in the patriarchal sense, but of reconciliation with oneself, with corporeality, with pleasure, with the right to exist in light.

She is a reminder that liking yourself is not a sin, but freedom.

Desiring yourself is an act of wholeness.

MetaSelf calls her a figure of femininity beyond the stereotype, the one who is both fragile and unshakable.

MetaSelf, through its Aphrodite, offers an answer: what remains is what no one can take away: the inner center of attraction, life and light.